Crossfade Picture House

Spring 2021

Advisor: Sean Canty

Advisor: Sean Canty

Cut vs. Crossfade

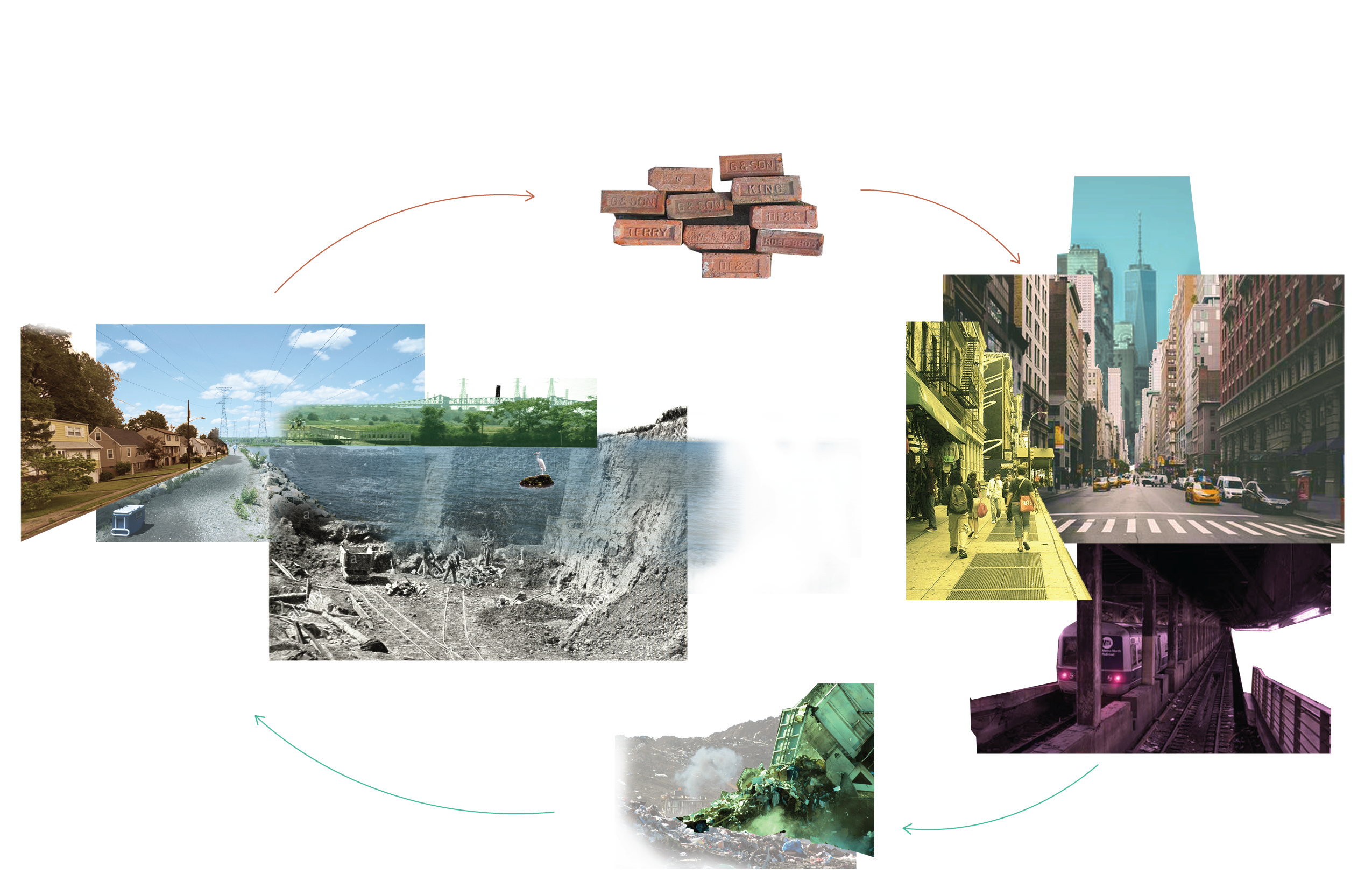

Crossfade as an editing technique is gradual and smooth when compared with a cut, where the transition is drastic. This picture house project takes this metaphor to reimagine the institution and its context. The traditional black box screens commercial cinema as spectacles, which pacify social issues and prevents radical transformation. This archetype denies the fact that cinema is deeply situated in the material world, and its production is highly industrial and social.

A crossfade picture house challenges the dialectics between cinematic illusion and reality by applying a gradual and subtle transition over time and space. The hard boundary of the theater black boxes start to pixelate, dissolve, and blend with the reality. Crossfading the context with the films being shown, the picture house invites and empowers the spectators to see the artifact while putting in an effort in recognizing and critiquing film as a part of reality.

Crossfade as an editing technique is gradual and smooth when compared with a cut, where the transition is drastic. This picture house project takes this metaphor to reimagine the institution and its context. The traditional black box screens commercial cinema as spectacles, which pacify social issues and prevents radical transformation. This archetype denies the fact that cinema is deeply situated in the material world, and its production is highly industrial and social.

A crossfade picture house challenges the dialectics between cinematic illusion and reality by applying a gradual and subtle transition over time and space. The hard boundary of the theater black boxes start to pixelate, dissolve, and blend with the reality. Crossfading the context with the films being shown, the picture house invites and empowers the spectators to see the artifact while putting in an effort in recognizing and critiquing film as a part of reality.

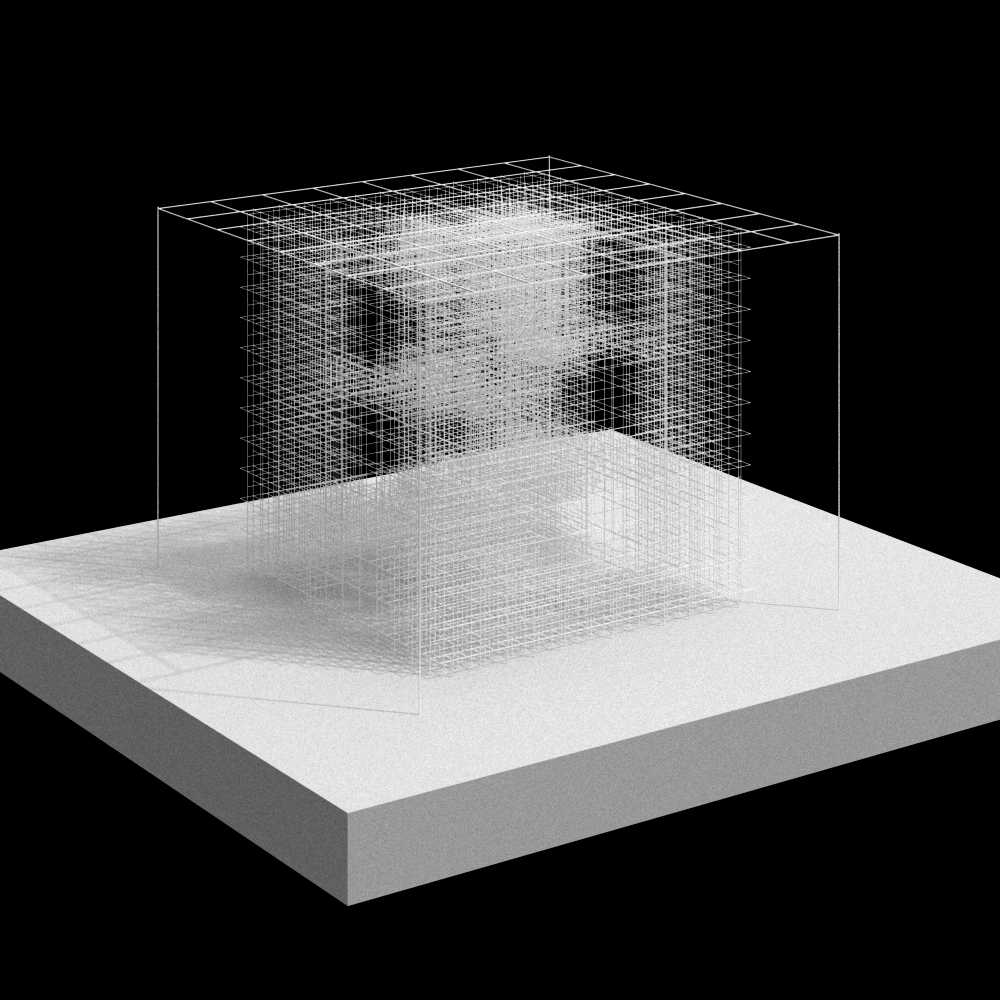

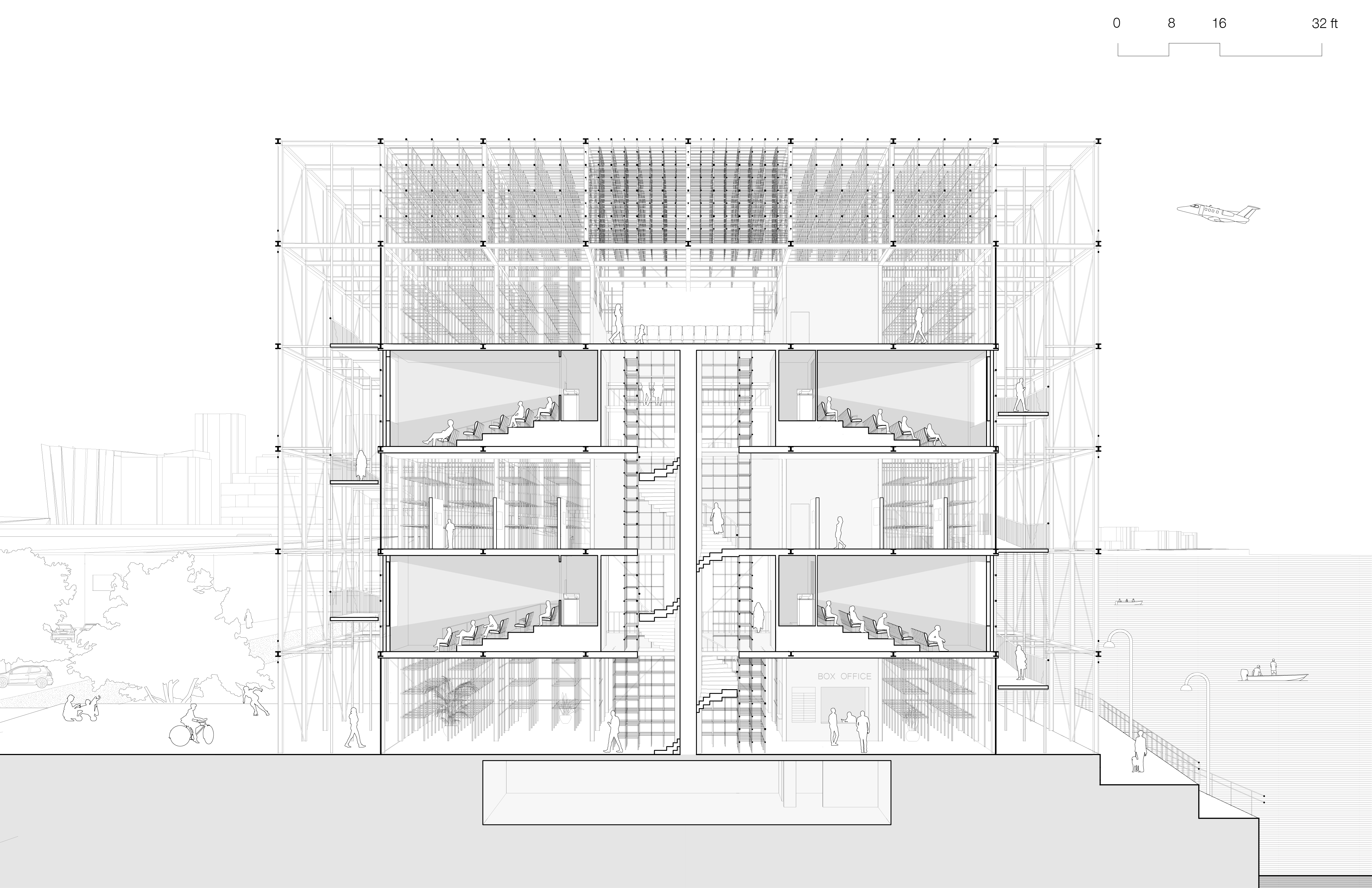

Spatializing Crossfade

A set of nested spatial grids serves as the structure of the building and frames the space within. The grid densifies towards the center, allowing the cinematic illusion to gradually materialize as one approaches the picture house, and gently fade out as one leaves. The members intentionally appear fragile, ephemeral and penetrable. Depending on the viewpoint and the time of day, the frame offers a range of views, from transparent see-through, where the frame almost disappears, to opacity where the frame is more materially present. The theaters and other public programs are housed within the voided out spaces within the frame.

A set of nested spatial grids serves as the structure of the building and frames the space within. The grid densifies towards the center, allowing the cinematic illusion to gradually materialize as one approaches the picture house, and gently fade out as one leaves. The members intentionally appear fragile, ephemeral and penetrable. Depending on the viewpoint and the time of day, the frame offers a range of views, from transparent see-through, where the frame almost disappears, to opacity where the frame is more materially present. The theaters and other public programs are housed within the voided out spaces within the frame.

Filters made of metal meshes intensify the crossfading effect. On each floor, they are inserted within the unprogrammed

interstitial space at the corners populated by the grid. Visitors

can access these unprogrammed areas via catwalks that lead from the public

space into these crossfading zones. Views parallel to the filters becomes

completely uninterrupted, while views perpendicular to them becomes obscured.

Views to the outside and at the theaters become more difficult to distinguish

because of this crossfading effect.

This effect changes at different times of

the day, as daylight and light fixtures within makes part of the building

appear dematerialized and crossfaded.

Experiencing Crossfade

Ascending and descending the spiral staircase at the center, or the smooth ramp at the periphery, the spectators’ visit to the picture house is always accompanied by the grid and its fuzzying crossfade effect. Moving in, out, below, and around them synchronizes the hi-res and low-res, the visitors and their view of inside-out at the city and outside-in at the cinematic illusion are constantly being framed, reframed, pixelated, and crossfaded. The conventional border of the theater blackbox dissolves as a full picture of the mixed reality emerges.

The picture house reconceptualized through crossfades dematerializes the distinction between cinematic illusions and the reality, allowing it to be seen as part of both both conceptually and materially. Moving in, out, below, and around the grid and the filters, the picture house synchronizes the hi-res and low-res, the image and its technical and digital support, and the reality and the simulachrum. The consumerist pacifying machine of illusions is transformed to an educational venue where reflection, discussion and critique of reality takes place in its interstitial spatialized form.

Ascending and descending the spiral staircase at the center, or the smooth ramp at the periphery, the spectators’ visit to the picture house is always accompanied by the grid and its fuzzying crossfade effect. Moving in, out, below, and around them synchronizes the hi-res and low-res, the visitors and their view of inside-out at the city and outside-in at the cinematic illusion are constantly being framed, reframed, pixelated, and crossfaded. The conventional border of the theater blackbox dissolves as a full picture of the mixed reality emerges.

The picture house reconceptualized through crossfades dematerializes the distinction between cinematic illusions and the reality, allowing it to be seen as part of both both conceptually and materially. Moving in, out, below, and around the grid and the filters, the picture house synchronizes the hi-res and low-res, the image and its technical and digital support, and the reality and the simulachrum. The consumerist pacifying machine of illusions is transformed to an educational venue where reflection, discussion and critique of reality takes place in its interstitial spatialized form.

Like Chair

Spring 2021

Collaborator: Weichen Wang, Vincent Dassault

Advisor: Jonathan Grinham

Collaborator: Weichen Wang, Vincent Dassault

Advisor: Jonathan Grinham

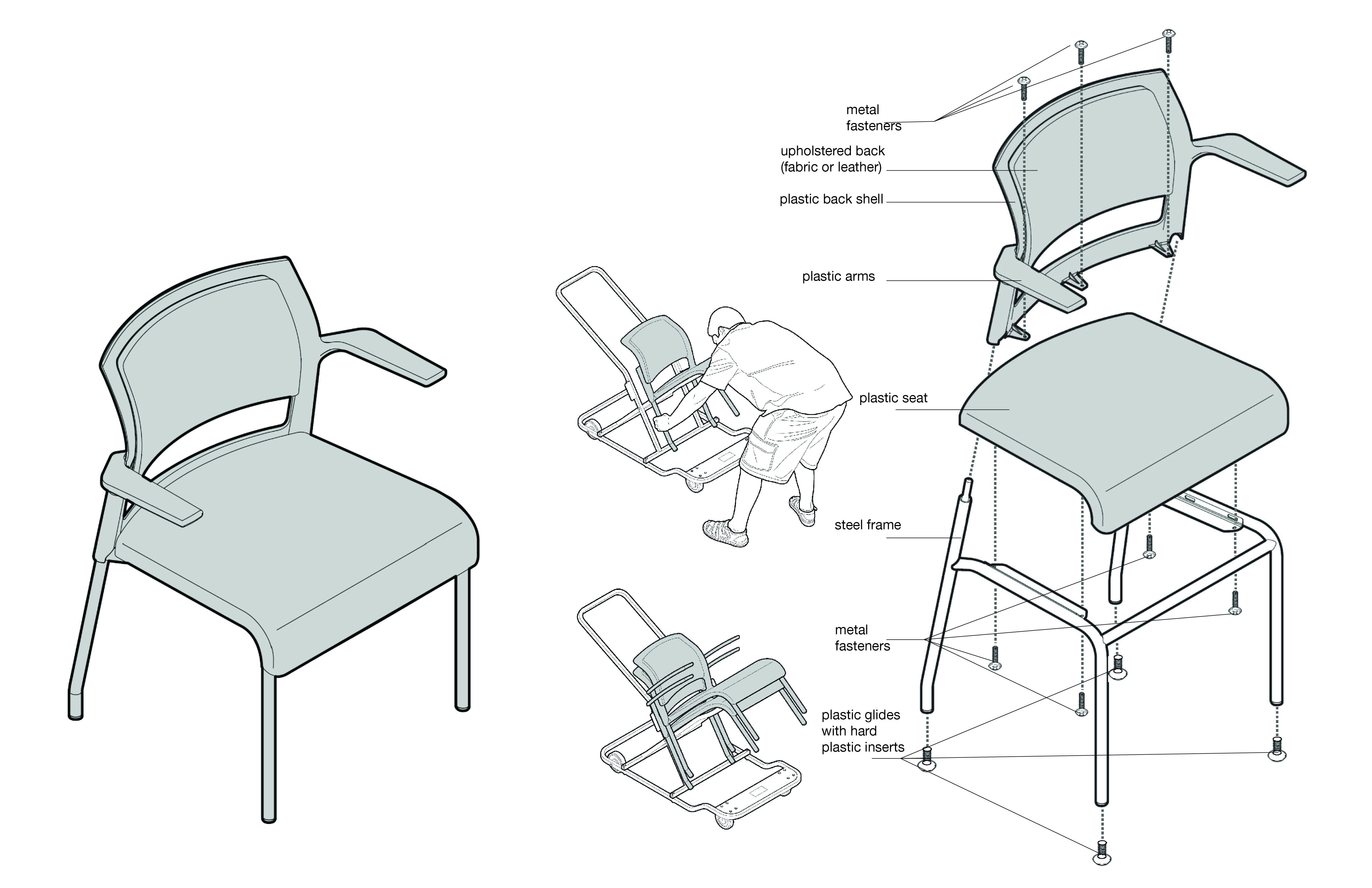

As a final project for the course in materials, this project stems from a detailed research and analysis of the Steelcase “Move” chair. Our research and analysis of the “Move” chair identifies it as an all-purpose chair with the convenience to be stacked to save space when not in use. Materially, this is supported by a sculptural PVC chair body and stainless steel frame. This design is not as practical during quarantine when demands for chairs dropped in work space and stacking is not a optimal solution in domestic settings.

With the context of post-pandemic scenarios in mind, our redesign focuses on the flexible and multi-use nature for both individual and shared seating, while maintaining the original Move chair’s compactness in storage. The intention is to create a chair that accommodates human interaction while allowing plenty of room for distancing. This led to our proposal of a chair that unfolds like origami. Depending on the degree of unfolding, the “Like” chair can accommodate 1-4 person and can be easily collapsed and stored. The profile of the chair is traced from “Move” chair when the curve is embedded into a thumbs up icon, giving the “Like” chair a playful character while maintaining the optimized ergonomic experience.

The material for the chair body can be sourced from recycled leftover textile during furniture manufacturing and production process. Variety and randomness in the found textiles offers a unique and dynamic texture to the “Like” chair. The chair body is capped with organic laminated oak with a low carbon footprint. We hope that through the playful yet practical proposal, we can reverse the downcycling convention in product design into an upcycling one, therefore improving a chair’s life cycle cost.

This was a group project. I worked mainly on the analysis and concept, designing the chair and the scene, and refining the Grasshopper algorithm.

With the context of post-pandemic scenarios in mind, our redesign focuses on the flexible and multi-use nature for both individual and shared seating, while maintaining the original Move chair’s compactness in storage. The intention is to create a chair that accommodates human interaction while allowing plenty of room for distancing. This led to our proposal of a chair that unfolds like origami. Depending on the degree of unfolding, the “Like” chair can accommodate 1-4 person and can be easily collapsed and stored. The profile of the chair is traced from “Move” chair when the curve is embedded into a thumbs up icon, giving the “Like” chair a playful character while maintaining the optimized ergonomic experience.

The material for the chair body can be sourced from recycled leftover textile during furniture manufacturing and production process. Variety and randomness in the found textiles offers a unique and dynamic texture to the “Like” chair. The chair body is capped with organic laminated oak with a low carbon footprint. We hope that through the playful yet practical proposal, we can reverse the downcycling convention in product design into an upcycling one, therefore improving a chair’s life cycle cost.

This was a group project. I worked mainly on the analysis and concept, designing the chair and the scene, and refining the Grasshopper algorithm.

Analysis of the original Steelcase “Move” Chair

Grasshopper algorithm for generating the origami mechanism

Alternative Scene Setup and Sample Material Palette

Hidden Room: Narcissistic Deflections

Fall 2020

Advisor: Michelle Chang

Advisor: Michelle Chang

This project investigates hiddenness as the deceptive character of frontality in architecture. Through manipulating the frontal façade, the fenestration, and glass panels, the spectator’s expectation of what lies behind the frontal façade is negated. Meanwhile, the façade becomes a screen where unexpected and disorienting space is projected.

My interest in video installations led me to researching the works by Peter Campus, Bruce Nauman, and Sarah Oppenheimer. In Campus’s work, our cultured tendency to inhabit the vantage point of the camera or the perspective projection is denied. In the single-channel video installation Three Transitions, Campus filmed himself piercing through a yellow backdrop (or front drop) with two cameras on either side of the backdrop. These two recordings are then overlayed on top of each other, creating a doubled vision that is disorienting and impossible for the spectator, who in reality cannot be physically at both the front and the back. As Rosalind Krauss argues, this spectacle runs counter to the narcissism afforded by live-feed video recording in mass media, and it produces two invisibilities for the spectator. Specifically, the spectator needs to determine their own position, choosing between either the objective reality or the mediated representation of it. A similar idea of double invisibility can be found in Michel Foucault’s analysis of the painting Las Meninas. This research inspired me to reflect on the duality of physical space and their representation in architecture which run parallel to each other, which translates to this hidden room project.

My interest in video installations led me to researching the works by Peter Campus, Bruce Nauman, and Sarah Oppenheimer. In Campus’s work, our cultured tendency to inhabit the vantage point of the camera or the perspective projection is denied. In the single-channel video installation Three Transitions, Campus filmed himself piercing through a yellow backdrop (or front drop) with two cameras on either side of the backdrop. These two recordings are then overlayed on top of each other, creating a doubled vision that is disorienting and impossible for the spectator, who in reality cannot be physically at both the front and the back. As Rosalind Krauss argues, this spectacle runs counter to the narcissism afforded by live-feed video recording in mass media, and it produces two invisibilities for the spectator. Specifically, the spectator needs to determine their own position, choosing between either the objective reality or the mediated representation of it. A similar idea of double invisibility can be found in Michel Foucault’s analysis of the painting Las Meninas. This research inspired me to reflect on the duality of physical space and their representation in architecture which run parallel to each other, which translates to this hidden room project.

Urbanism Studies

Spring 2021

A series of visual exercises in representing the urban transformation taking place in Cambridge, MA and Boston across time. In a comic-like style, the studies seek to represent gentrification and homogeneity that comes with urban sprawl, and propose alternative to transform post-industrial lands into community hubs.

Interactive Elastic Structure

Fall 2017

Advisor: Axel Kilian

Advisor: Axel Kilian

This project is a prototype for an interactive architecture concept. Integrating parametric design, electronics, the one-person enclosure uses a tensegrity structure that redefines space by responding to the environment and how it is inhabited. A canopy partition, defined by strings in the prototype, partitions the top and bottom spaces. When the top space is inhabited, the pressure sensor is triggered and controls the pulleys to unwind the strings and lower the canopy. After the pressure from the top is removed, the sensor controls the pulleys to wind the strings back, thus lifting the canopy and make the bottom space occupiable. The result is a structural system that has a light and elegant appearance and is responsive to the different needs of the inhabitants.

conceptual references

conceptual references

Climate Park of Brick Monuments

Spring 2019

Advisor: Mario Gandelsonas

Advisor: Mario Gandelsonas

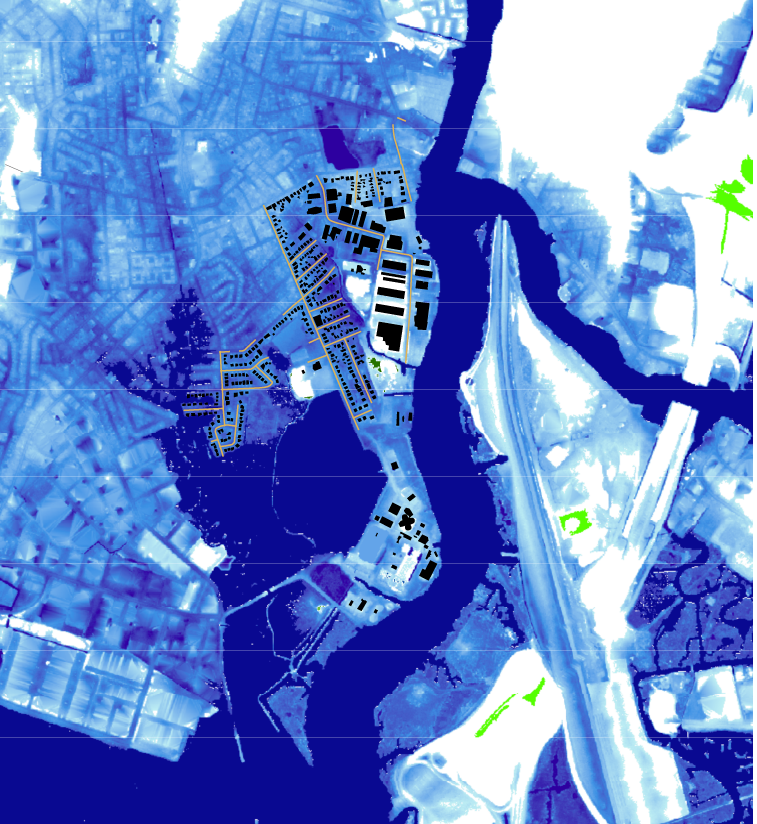

In the Fourth Regional Plan of 2018, the Regional Plan Association (RPA) proposed designating the NJ Meadowlands as a “Climate Park”. Adjacent to Manhattan, the Meadowlands and the 15 municipalities that fall within it is one of the Northeast’s largest remaining contiguous tracts of urban open space and a crucial “sponge” to mitigate rising sea levels. It also supports a wide array of wildlife and biodiversity in tandem with transportation and freight infrastructure vital to the economy.

Little Ferry, one of the 15 municipalitieson the site of this project, lies in the northeast of the meadowlands on the bank of Hackensack River. As elsewhere in the meadowlands, the history and landscape of the town is marked by urbanization in the New York metropolitan area, both positively and negatively.

![]()

Little Ferry, one of the 15 municipalitieson the site of this project, lies in the northeast of the meadowlands on the bank of Hackensack River. As elsewhere in the meadowlands, the history and landscape of the town is marked by urbanization in the New York metropolitan area, both positively and negatively.

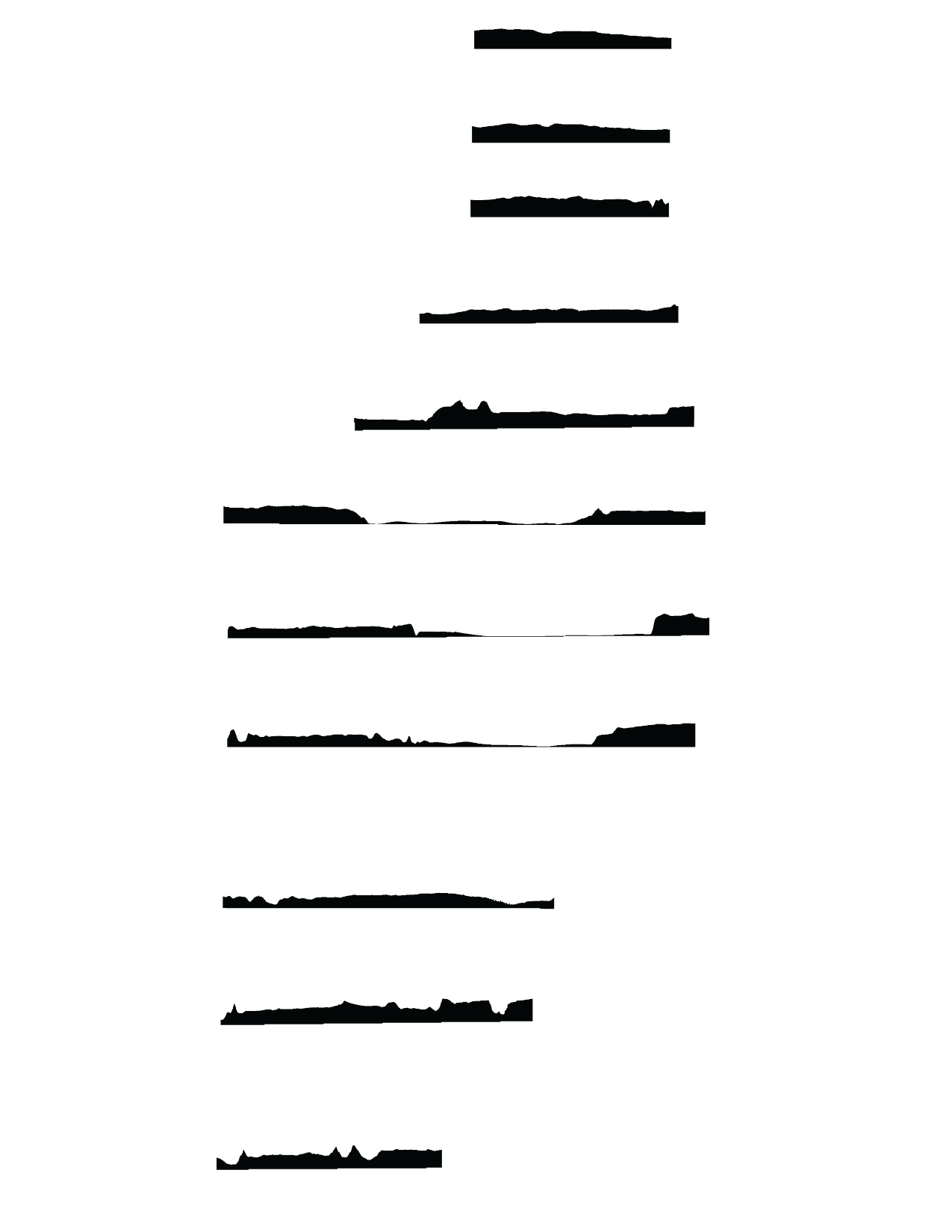

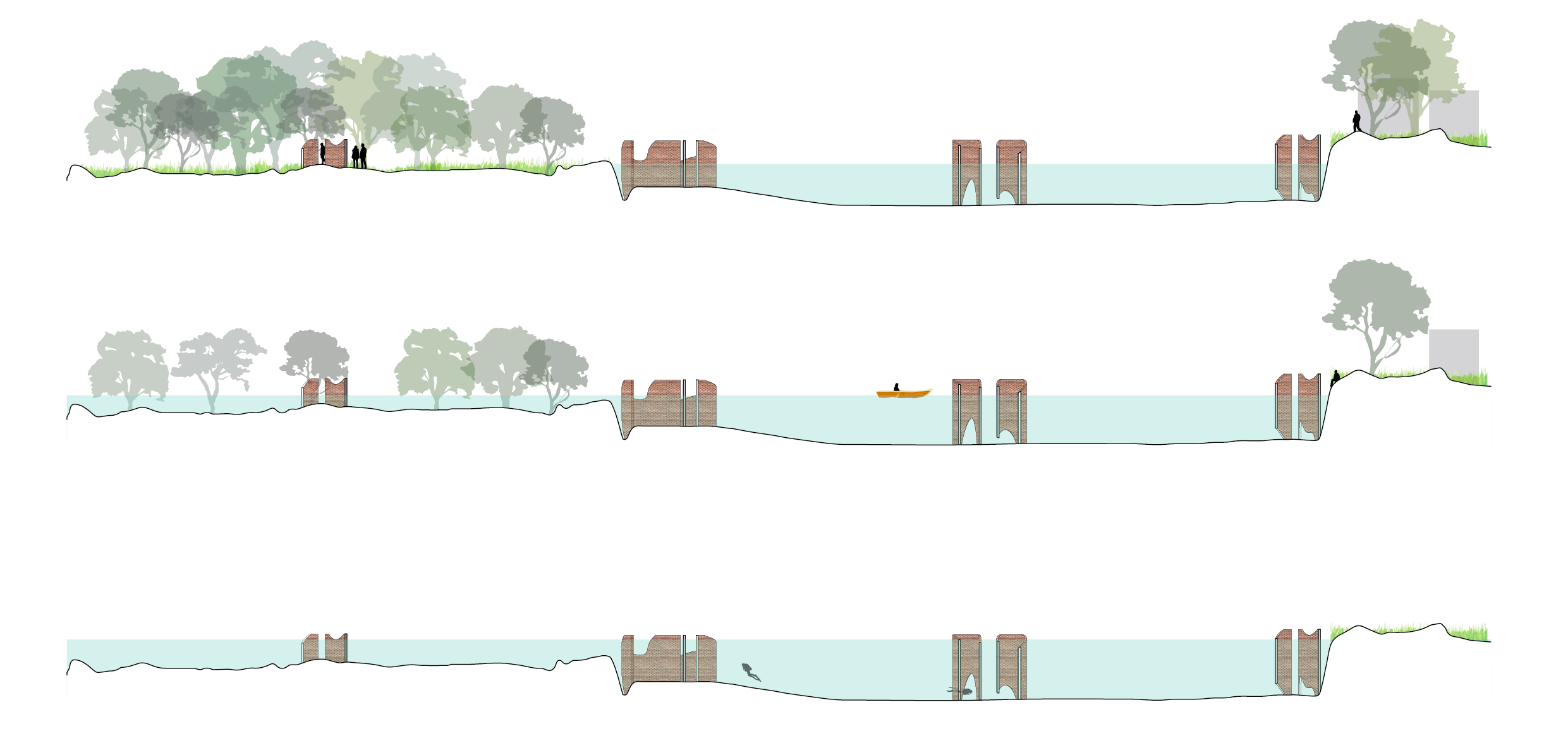

Sea level rise threatens the biodiversity and the daily lives of the local inhabitants. Recent research indicates that the region will be gradually inundated by the end of this century.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Left to right: current sea level; +1 ft (2030); +3 ft (2100); +6 ft

Left to right: current sea level; +1 ft (2030); +3 ft (2100); +6 ft

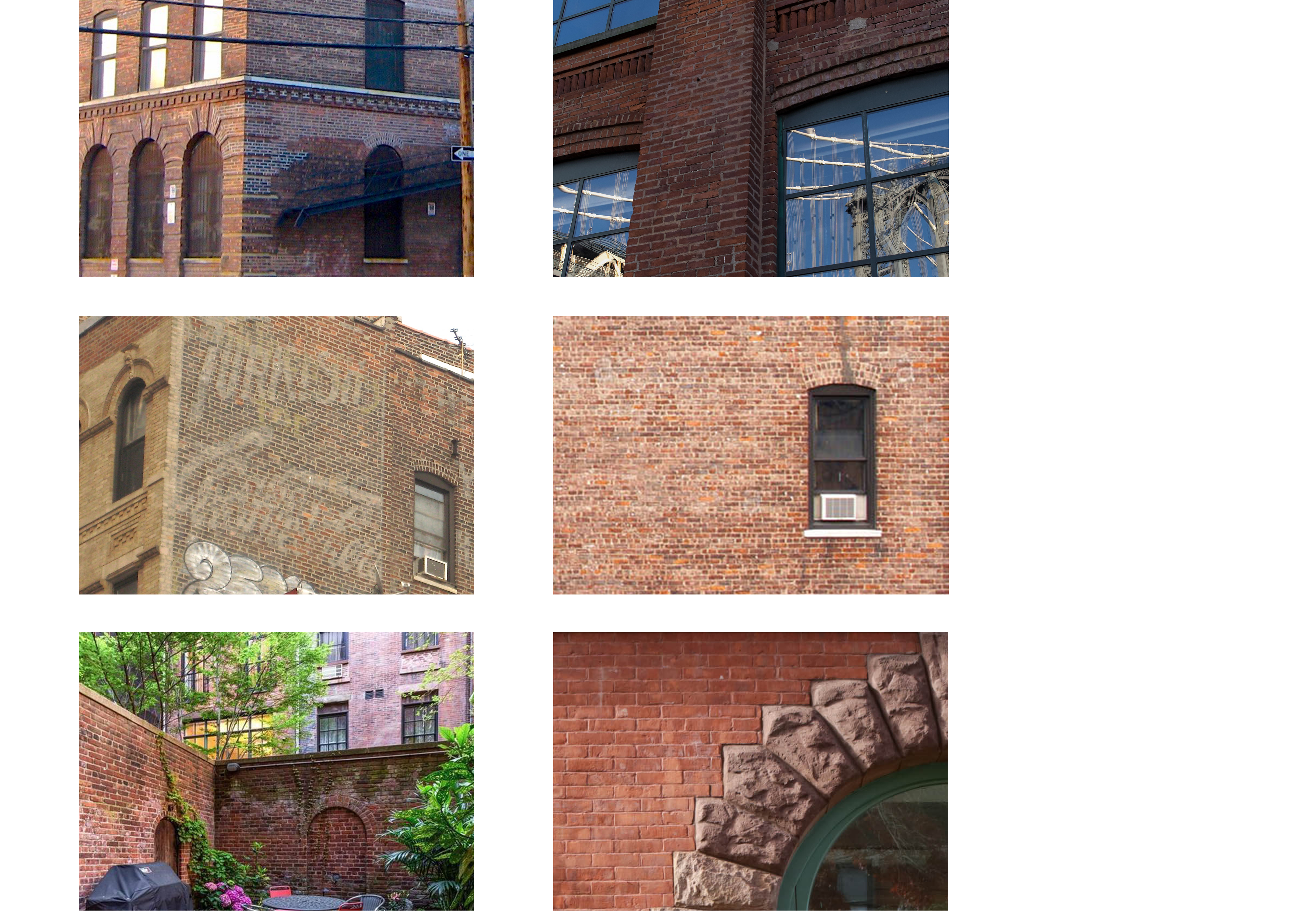

Little Ferry started as an important ferry crossing for towns in Hackensack and Bergen. Its easy access to water supported clay industry as the major source of local income.

Mehrhof Pond, the pond at the center of the town, was formerly the largest clay pit used for brickmaking. The Mehrhof’s were a major family in the brick business. A brick manufacturing company occupied the property until the 1940’s. It is now filled with fresh water.

![]()

Mehrhof Pond, the pond at the center of the town, was formerly the largest clay pit used for brickmaking. The Mehrhof’s were a major family in the brick business. A brick manufacturing company occupied the property until the 1940’s. It is now filled with fresh water.

Brick buildings in NYC

Brick buildings in NYC

“Little ferry became a hotbed of activity in the brick industry due to its extensive beds of clay which led to hundreds of people being employed in the brickyards. Bricks on barges floating down the Hackensack River were a common sight.”1

“Many more brick companies would find their place in Little Ferry. In 1895, the combined output of the four large yards reached 100,000,000 bricks annually, making Little Ferry the second largest producer in the United States.”2

1 Gonzalez, Laura. “Little Ferrys Brick Yards.” STREET TO THE LEFT, 8 July 2016, streettotheleft.weebly.com/blog/little-ferrys-brick-yards.

2 Sue. “Just Another Brick in the Marsh: Finding Little Ferry’s Historic Clay Industry.” Just Another Brick in the Marsh: Finding Little Ferry’s Historic Clay Industry, 9 July 2013, www.hiddennj.com/2013/07/just-another-brick-in-marsh-finding.html.

![]()

![]() The Clay and Brick Industry in New Jersey

The Clay and Brick Industry in New Jersey

“Many more brick companies would find their place in Little Ferry. In 1895, the combined output of the four large yards reached 100,000,000 bricks annually, making Little Ferry the second largest producer in the United States.”2

1 Gonzalez, Laura. “Little Ferrys Brick Yards.” STREET TO THE LEFT, 8 July 2016, streettotheleft.weebly.com/blog/little-ferrys-brick-yards.

2 Sue. “Just Another Brick in the Marsh: Finding Little Ferry’s Historic Clay Industry.” Just Another Brick in the Marsh: Finding Little Ferry’s Historic Clay Industry, 9 July 2013, www.hiddennj.com/2013/07/just-another-brick-in-marsh-finding.html.

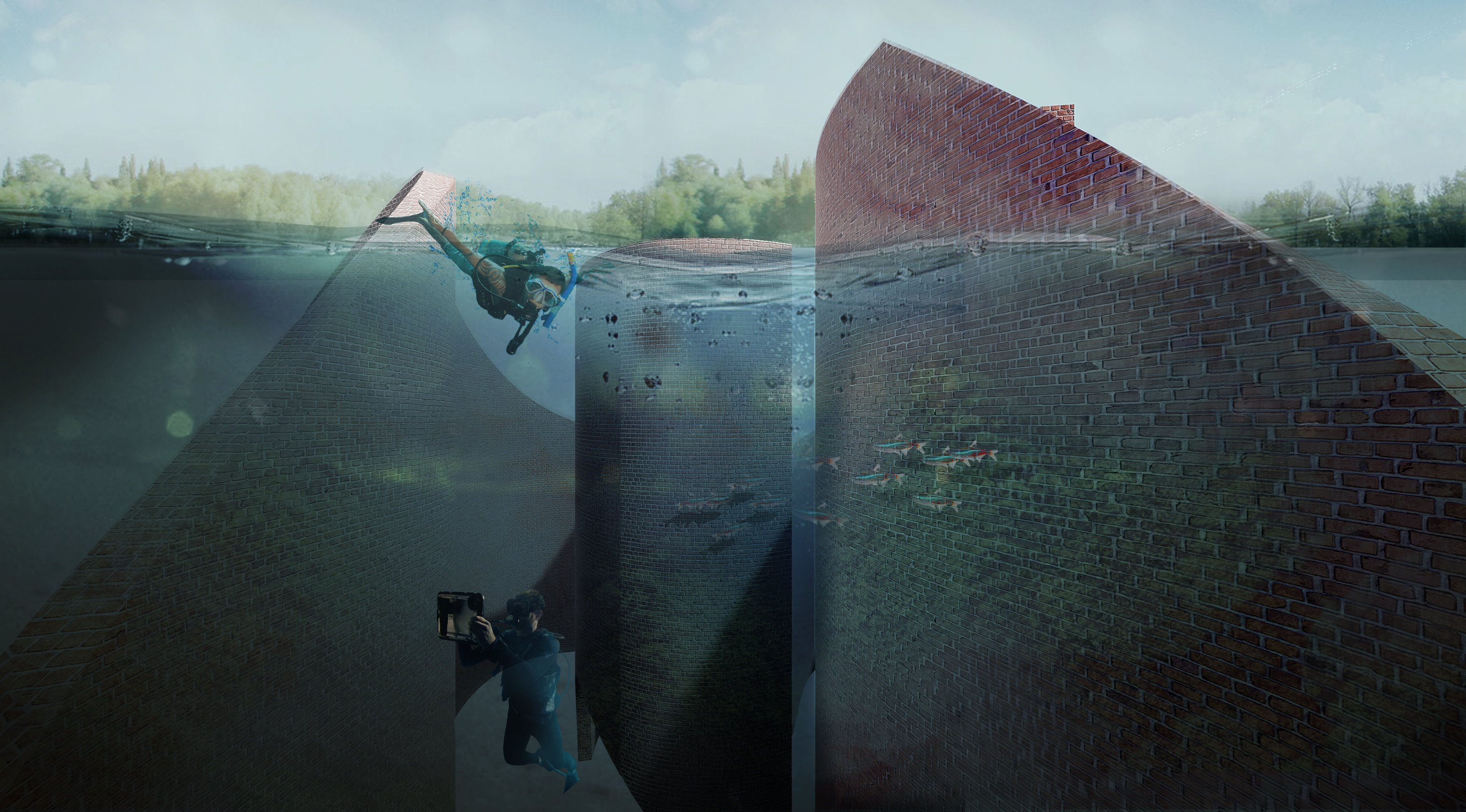

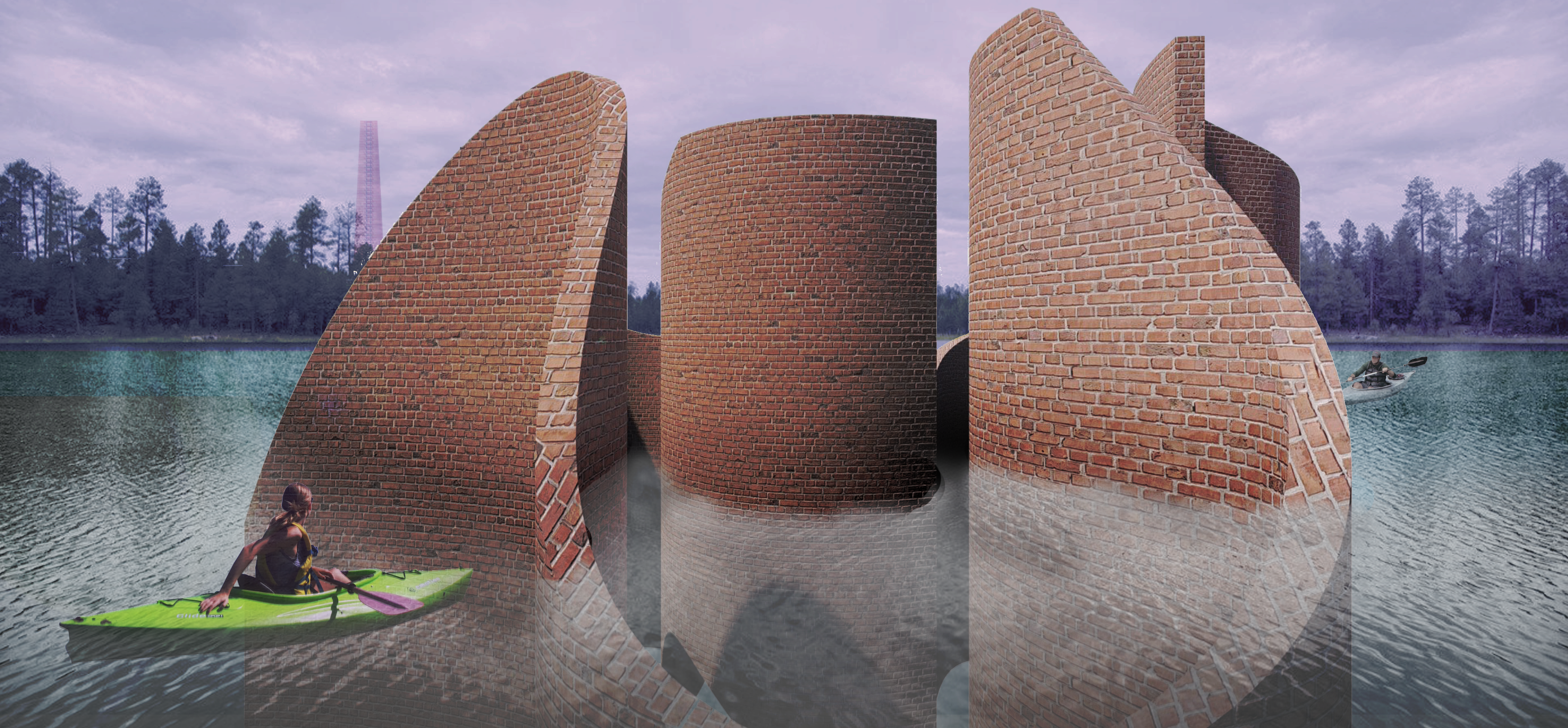

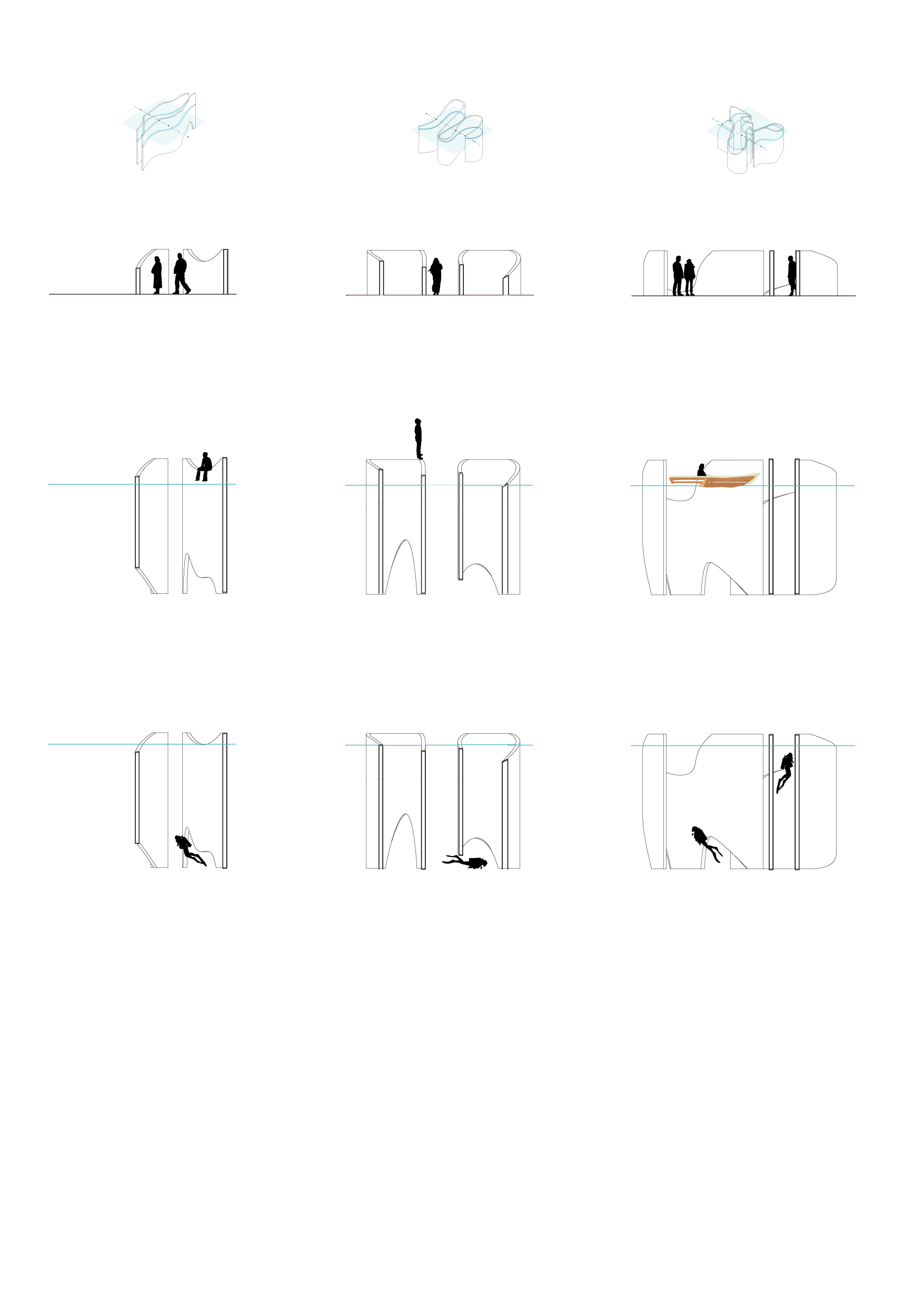

In the proposed park in Little Ferry, a series of brick monuments will be erected. It is intended that as the sea level rises, these monuments serve as sites for contemplation over human activities and the impact on the environment. In a posthuman scenario, these monuments become the memorial of the underwater town.

Monuments are consistently placed apart from each other at the nodes of a grid system derived from the road network.

Monuments are consistently placed apart from each other at the nodes of a grid system derived from the road network.

The base and top curves of the monuments are designed to interact with the water surface, revealing different shapes of the monuments that demands distinct means of access at each stage of inundation.